As I was contemplating what to write for this week’s post, I learned that a final agreement had been reached between the California legislature and Governor Gavin Newsom to pass SB 276, a bill designed to close loopholes in SB 277, the California law passed in 2015 to eliminate nonmedical “personal belief exemptions” to school vaccine mandates. As I read about SB 276, it occurred to me that we’ve written almost nothing about the bill here at SBM, other than to mention in April that it had been introduced in the California Senate by Senator Richard Pan, the same Senator who had co-sponsored SB 277.

It occurred to me that this would be a good opportunity to examine how we got to this point, some of the shenanigans pulled by Gov. Newsom, both earlier in the process of getting SB 276 passed and last week at the last minute as it was passed by the Assembly and Senate, and the reaction of the antivaccine movement to the bill.

A brief history of vaccine mandates

The success of vaccination campaigns depends upon as many members of an at-risk population as possible being vaccinated in order to achieve herd immunity. Herd immunity (these days more frequently known as community immunity, given that people don’t like being compared to cattle) has been discussed on this blog many times, most prominently by Drs. Mark Crislip and Joseph Albietz (both of whom, alas, no longer write for SBM). Basically, when a sufficiently large percentage of the population is vaccinated against a disease, even those not immune to the disease obtain a measure of protection against infection because the immunity of a large percentage of the population prevents the infectious agent from being readily spread from person to person. The agent thus never gets a “foothold” in the community, and the greater the proportion of the population vaccinated the less the chance of a susceptible individual coming into contact with an individual carrying the infection. Community immunity is very important because it helps to protect population members who can’t be vaccinated for whatever reason, be it immunodeficiency or other medical reason or because they are too young to be vaccinated. Vaccines aren’t perfect. Even highly effective vaccines only protect 90 to 100% of the vaccinated population. The precise percentage of the population that needs to be vaccinated to achieve herd/community immunity varies depending upon the efficacy of the vaccine and the infectiousness of the disease being vaccinated against, but a good, serviceable ballpark estimate is usually somewhere in the 90% and above range.

Community immunity is the reason why it is so important to vaccinate as large a percentage of the at-risk population as possible. To this end, public health officials have at times tried a number of strategies, ranging from cajoling to compulsory vaccination. A different strategy to achieve high rates of vaccination is the imposition of vaccine mandates. School vaccine mandates differ from laws requiring vaccination in that no one from the state will hunt parents down to force them to vaccinate. However, if parents want to take advantage of state services such as public schools for their children, or if they want to use services that place a lot of children together (such as day care facilities), they have to have their children vaccinated. This is a practice with very old precedent. For example, in 1827 Boston became the first city to require parents of children enrolling in public school to present evidence of vaccination against smallpox. The trend continued, as described in this review of school vaccine mandates:

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts incorporated its own school vaccination law in 1855, New York in 1862, Connecticut in 1872, and Pennsylvania in 1895. Other Northeast states soon passed their own requirements. The trend toward compulsory child vaccination as a condition of school attendance eventually spread to states in the Midwest [e.g., Indiana (1881), Illinois and Wisconsin (1882), Iowa (1889)], South [e.g., Arkansas and Virginia (1882)], and West [e.g., California (1888)], though not without considerable political debate.

School vaccine mandates, although they were opposed by antivaccination leagues from the beginning, tended to provoke less virulent opposition and better compliance than compulsory vaccination, making them not only politically more palatable, but more effective. However, over the last couple of decades the effectiveness of school vaccine mandates has been weakened by a steady expansion of non-medical exemptions, in particular religious or philosophical exemptions, a trend that has only recently started to reverse. Examples include: California passing SB 277, which eliminated PBEs altogether; Washington passing HB 1638, which removes the PBE for the MMR vaccine requirement for public schools, private schools and day care centers; Maine passing HB 586, which removes personal and religious belief exemptions for public school immunization requirements; and New York passing SB 2994, which removes the religious exemption for public school immunization requirements. Currently, 45 states allow religious exemptions that vary in requirements, while 15 states currently permit philosophical exemptions, in which parents must declare a personal belief against or philosophical objection to vaccination. Usually, parents must file a form, ranging from just once to annually, with their school district stating their personal objection to vaccination. Not surprisingly, in states that allow personal belief exemptions they are the most commonly invoked reason by parents to refuse vaccinating their children, as the number of children who qualify for medical exemptions is quite small.

The problem with personal belief exemptions

The problem with PBEs, of course, is that they can be abused, and, when antivaccine misinformation spreads, provide a mechanism by which vaccination rates plummet, leading to local populations with low vaccination rates. That’s exactly what happened in California and is happening in Texas now, so much so that I not-infrequently say that when the next big US measles outbreaks happen, they’ll probably happen in Texas. In California before SB 277, for instance, although statewide the percentage of children with parents claiming the personal belief exemption remained low, there were schools where exemption rates climbed as high as 58% (one kindergarten reported a 76% exemption rate) serving as incubators for outbreaks of measles and other contagious diseases. After all, unvaccinated children have a 23-fold higher risk of contracting pertussis and a 35-fold higher risk of contracting measles than vaccinated children. Unfortunately, non-vaccinating populations tend to cluster, and their refusal of vaccines leads to there being areas with large pockets of unvaccinated children, ripe for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

How can states decrease the number of PBEs? There have traditionally been two approaches. One is to make PBEs more difficult to obtain than parents just signing a form, usually coupled with education. The other is to eliminate PBEs altogether. California tried the first approach before resorting to the second approach. PBEs are critical, too, as it has been shown on more than one occasion that states with more permissive laws regulating the granting of PBEs contribute to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

AB 2109: Education before granting a PBE

Faced with the rising number of PBEs and schools with alarmingly low vaccine uptake rates, in 2012 the California legislature passed AB 2109. All AB 2109 mandated was, in essence, informed consent. Under AB 2109 parents were required to obtain a signed form from a pediatrician stating that they had been counseled on the risks and benefits of vaccines. The law, in essence, required that the parents make such a monumental decision as not to vaccinate their child only after having had a physician provide them with informed consent, so that they understood the potential consequences of not vaccinating, as well as the risk-benefit ratio for vaccination.

In response to years of abysmal vaccine uptake rates and multiple outbreaks, particularly a large pertussis outbreak in 2012, out of which was born a campaign by a mother whose baby died of pertussis to increase vaccine uptake, in 2014 the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services altered the regulations regarding requirements for parents to claim personal belief exemptions to vaccine mandates, patterning its policy change on AB 2109. Basically, starting January 1, 2015, any parent seeking a PBE was required to travel to their local county health office in order to:

- Be educated by a local health worker about the benefits of vaccination and the risks of disease.

- Sign the universal state form that includes a statement of acknowledgement that parents understand they may be putting their own children and others at risk by refusing vaccinations. Only the official state form is now permitted. No substitute forms are allowed any more, as they were in the past.

The rule change worked, too. PBE rates declined. However, even this rule change has led to a backlash among antivaxers, to the point where there have been attempts to “make measles great again” in Michigan by passing a law to eliminate the authority of the MDHSS to require this educational program and standardized form before a PBE will be issued. Fortunately, both attempts have failed, and there are unlikely to be any more serious attempts to eliminate the requirement, at least not while the current governor is in office. There was also similar resistance to AB 2109 in California, and unfortunately then-Governor Jerry Brown even issued a signing statement intended to water down the effect of the law by exempting parents seeking religious exemptions from the requirement to seek counseling from a physician and have the physician sign the form. It was truly a betrayal of California’s children.

Thus the stage was set for SB 277.

The Disneyland measles outbreak: Everything changes

As you can see, even a minor change in the law, such as AB 2109, stirred up fierce opposition and led a governor whose previous record in health care was quite good to betray California’s children by trying to water down the newly enacted law as a sop to religion. Obviously, the best solution to the problem of pockets of unvaccinated children due to vaccine hesitancy or refusal was to eliminate religious and other nonmedical vaccine exemptions. The problem was then that the political climate was not ripe for a law eliminating nonmedical exemptions, even though, from a public health standpoint, that would be the most effective intervention.

Then, beginning right after the Christmas holiday in 2014 and extending into 2015, an incident occurred that changed everything, at least in California: the Disneyland measles outbreak. By the time the outbreak had subsided, there had been 147 cases of measles, 133 in California and the rest in six other states, Mexico, and Canada. Public health officials believe an individual infected with the measles virus visited the Disney resort at some point between December 15 and 20, 2014, and the spread of the disease was linked to low vaccine uptake rates. Of note, in Canada, one child who was infected at Disneyland returned to a susceptible religious community near Montreal and sparked a secondary outbreak there. Of the cases whose vaccination status had been verified, 70% were unvaccinated, with 48% having a PBE and 28% being too young.

In February 2015, while the outbreak was still raging, Sen. Richard Pan, a pediatrician turned politician, introduced SB 277, a bill to eliminate nonmedical exemptions to school vaccine mandates. Over the next four months the State of California was consumed by controversy, as antivaxers pulled out all the stops to try to stop passage of the bill. If you think antivaxers were loud, persistent, and unhinged in 2012, they topped themselves in 2015. As SB 277 advanced through the California legislature, the usual suspects just about lost it, with Barbara Loe Fisher likening the bill to medical blackmail and invoking Elie Wiesel, just in case you don’t get the message that she thinks California was dealing in Nazi-like fascism. Along the way, antivaccine celebrities like Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (who is also fond of Holocaust analogies) and Rob Schneider were trotted out with the same old pseudoscience and “health freedom” arguments, although RFK, Jr. might have done more harm to his cause than good when he explicitly likened the vaccine program to the Holocaust and was forced to apologize, although it was a classic “notpology.”

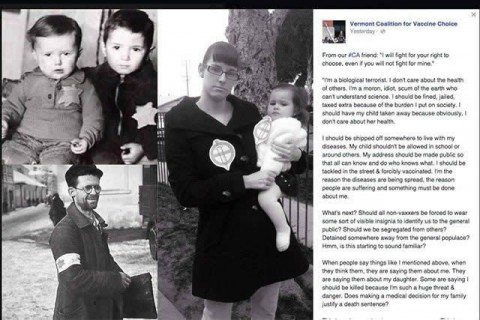

Along the way, we were also treated to images like this from Heather Barajas, who photographed herself and her child wearing badges shaped like a syringe juxtaposed with photos of Jews in Nazi Germany forced to wear yellow Stars of David:

The uproar was so great that Barajas was actually forced to take her offensive image down. I note that this is in marked contrast to this year, when antivaxer Del Bigtree donned a yellow Star of David, again likening antivaxers to Jews during the Holocaust and, in this case, the State of New York, to Nazis and proudly refused to back down.

Nonetheless, as pessimistic as I was about its chances of passage, SB 277 was indeed ultimately passed by the California legislature and signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown, who in doing so redeemed himself for his AB 2109 debacle. The law worked, too, at first. After the start of the 2016 school year, when SB 277 went into effect, PBE rates fell, although medical exemption rates did increase slightly. This increase was thought to be due to parents whose children needed medical exemptions and found it to inconvenient to get a doctor’s letter and instead opted just to claim a PBE being forced to get a doctor’s letter and get a real medical exemption.

Unfortunately, it was not long before a major flaw in SB 277 reared its ugly head, which brings us back to SB 276, a bill meant to correct that serious flaw.

SB 276: Correcting the problem with SB 277

Before SB 277 had even gone into effect, I took note of a disturbing phenomenon. Antivaccine pediatrician Dr. Bob Sears was out and about giving talks to parents about how to avoid the provisions of SB 277. Eventually, it became apparent that one aspect of SB 277, which was a compromise to get the bill passed, was an enormous boon to antivaccine quacks. That provision allowed any physician to write a letter supporting a medical exemption to school vaccine mandates, and the state had to accept it as valid. Basically, any licensed doctor can list any reason he or she wishes to in a medical exemption letter, and there’s nothing in SB 277 that lets health authorities deny the exemption. The result was entirely predictable. There rapidly emerged a cottage industry of antivaccine and antivaccine-sympathetic doctors willing to write medical exemption letters based on indications not supported by science.

In reality, there are very few scientifically and medically valid reasons for a medical exemption. For instance, immunosuppressed children should not receive attenuated live virus vaccines, although they can still receive killed vaccines, and children with a history of anaphylaxis or severe allergic reactions in response to a vaccine component should not receive vaccines with that component again. (The complete list of contraindications to various vaccines can be found here.) It wasn’t long, however, before medical exemptions based on bogus “indications” were widely for sale, thanks to various antivaccine quacks. These bogus indications include—of course!—MTHFR mutations, family history of autism, family history of autoimmune disease, food allergies, celiac, type 1 diabetes, and a wide variety of other “contraindications to vaccination.” Predictably, after the initial improvement in vaccine uptake due to SB 277, soaring numbers of medical exemptions led to a reversal of that progress, thanks to a gold rush of antivaccine quacks. Indeed, antivax groups maintain lists of “vaccine-friendly” doctors willing to write dubious medical exemptions, many of whom advertise on various antivaccine sites their willingness to write medical exemptions. Dr. Sears himself generates what appear to be basically form letters in which he inserts whatever indications he wants. There are even examples of these letters that have been posted, while in the Bay Area, five doctors wrote one-third of all medical exemption letters.

Indeed, an observational study last year highlighted the problems public health officials and school nurses were having because of this. The key findings in the structured interviews with school and public health officials included (1) frustration over the lack of authority for local health departments, (2) concern over the burden on school staff to review medical exemptions, (3) frustration with physicians who are writing problematic medical exemptions, and (4) concern about an increase in medical exemptions under SB277. For example, here’s what one immunization coordinator said:

My frustration is dealing with these doctors that would write what is thought to be maybe not completely valid medical exemptions for the students whose parents just don’t want them to get any. That’s my personal frustration, and that is shared by a lot of school nurses

Indeed.

This brings us to SB 276, which is on the verge of finally being passed into law. In response to these problems, Senator Richard Pan, who co-sponsored SB 277 and was the driving force behind getting it passed, introduced SB 276, a law that would mandate a database of medical exemptions, so that the state can keep track of which doctors are issuing the most medical exemptions, and require that requests for medical exemptions to school vaccine mandates be approved by the State Public Health Officer or designee, who could reject exemptions not supported by science. The bill’s been watered down a bit since then, with amendments removing the provision that would authorize the State Health Officer to review medical exemptions and revoke the ones he deems fraudulent or inconsistent with medical guidelines. On the other hand, the bill would require that the state health department to provide a standardized form for use for medical exemptions:

This bill would instead require the State Department of Public Health, by January 1, 2021, to develop and make available for use by licensed physicians and surgeons an electronic, standardized, statewide medical exemption request that would be transmitted using the California Immunization Registry (CAIR), and which, commencing January 1, 2021, would be the only documentation of a medical exemption that a governing authority may accept. The bill would specify the information to be included in the medical exemption form, including a certification under penalty of perjury that the statements and information contained in the form are true, accurate, and complete. The bill would, commencing January 1, 2021, require a physician and surgeon to inform a parent or guardian of the bill’s requirements and to examine the child and submit a completed medical exemption request form to the department, as specified. By expanding the crime of perjury, the bill would impose a state-mandated local program.

The bill would also require the department to annually review immunization reports from schools, to identify schools with an overall immunization rate of less than 95%, physicians and surgeons who submitted 5 or more medical exemption forms in a calendar year, and schools and institutions that do not report immunization rates to the department. It would also require a clinically trained staff member who is a physician, surgeon, or a registered nurse to review all medical exemptions meeting these conditions, authorizing the State Public Health Officer to review the exemptions identified by that staff member as fraudulent or inconsistent with established guidelines. The department can report physicians issuing fraudulent or scientifically unjustified medical exemptions to the state medical board.

Not surprisingly, resistance has been fierce. Antivaxers have protested by cosplaying Star Wars characters at Disneyland and the terrorist V from V Is For Vendetta at San Diego Comic-Con. On a more dire and serious note, Sen. Pan started receiving death threats again, and was even assaulted on the streets of Sacramento by an antivaxer named Austin Bennett. Fortunately, it was relatively minor, a shove/hit to the back of the head, and Bennett did not persist. Then, two weeks ago there was a rather large (by antivax standards, anyway) demonstration at the California State Capitol Building. Out-of-state operatives linked to the Church of Scientology were brought in to help the opposition to SB 276. Meanwhile, a reporter for the L.A. Times screwed up massively and published a puff piece full of false equivalence about Dr. Bob Sears, who, predictably, has been one of the most prominent and vocal opponents of SB 276.

Despite all that, SB 276 passed the Assembly and the Senate anyway, and by large margins, which brings us to the latest drama.

What the heck is Governor Newsom playing at?

Even before the bill had hit his desk for his signature, Governor Gavin Newsom had suggested that he was unhappy with some aspects of it. It was a move that surprised backers of the bill, because previously Gov. Newsom had signaled that he would sign the bill once it was passed by the legislature:

Medical groups and a lawmaker behind California legislation to crack down on vaccine exemptions said Wednesday they were surprised by Gov. Gavin Newsom’s last-minute call for changes to the bill, a move that inserted fresh uncertainty into one of the year’s most contentious issues.

It was the second time the Democratic governor sought to change the measure aimed at doctors who sell fraudulent medical exemptions for students, a proposal vehemently opposed by anti-vaccine activists. After expressing hesitancy with the bill and winning substantial changes to the measure in June, Newsom had committed to signing it.

The Governor shocked SB 276 supporters with these two Tweets right after the Labor Day holiday weekend:

The Governor believes it’s important to make these additional changes concurrently with the bill, so medical providers, parents and public health officials can be certain of the rules of the road once the bill becomes law. #SB276 (2/2)

— Office of the Governor of California (@CAgovernor) September 3, 2019

What did it mean? And why was Newsom asking for more changes to a bill that he had previously indicated that he would sign, after having already insisted on changes that watered the bill down in June. That was when Newsom raised concerns that SB 276 would create a bureaucracy that would interfere with the doctor-patient relationship. His office negotiated changes with the bill’s sponsors to weaken the legislation. Instead of requiring the California Department of Public Health to approve all medical exemption requests, Newsom demanded that SB 276 narrow its focus to reviewing medical exemption requests from doctors who write five or more medical exemptions in a year and to requests coming from schools or day cares with immunization rates of less than 95%. After that, he said that he would “absolutely sign” the bill when it hit his desk.

After going back on his promise June, Newsom demanded more changes:

Newsom’s new demands go further than his initial amendments accepted by Pan and legislative leaders. One change would ensure that the state will not review medical exemptions granted before January 2020. That has stirred fears that it’ll lead to a mad rush on medical exemptions this year that state public health authorities won’t be able to retroactively scrutinize.

The governor also wants to strike SB 276 language that would require doctors to sign under penalty of perjury that they are not granting exemptions for financial gain.

Pan and other lawmakers were stunned by the late amendment request, which came on Twitter only a few minutes after the last major opportunity to amend the bill in the Assembly. With SB 276 headed to Newsom’s desk, the Legislature would have to insert the governor’s changes into a separate bill.

So why would Gov. Newsom go back on his word? It’s a reversal that could really harm him in future dealings with the legislature:

Political strategists from both parties say Newsom’s late tactics represent a remarkable political mistake for the new governor that could potentially harm his reputation and dampen his ability to govern.

“When you give your word and you make a deal, you’ve got to stand by it,” said Democratic strategist Dana Williamson, longtime adviser to former Gov. Jerry Brown. “Otherwise people will think twice the next time he says there’s a deal.”

Williamson said even if the governor learned new information or had a revelation about concerns over the policy, there are avenues like legislative “cleanup” bills to address outstanding issues. She also said announcing his reservations on Twitter was not the best course of action.

“I do think he could have picked up the phone,” Williamson said.

Rob Stutzman, a Republican strategist and former adviser to Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, said Newsom risks making enemies in the Legislature. He and Williamson couldn’t think of a similar situation faced by Brown or Schwarzenegger.

Reaction to Newsom’s flip-flop from mainstream media sources was virtually all very negative. I, too, wondered what the heck was going on. Did Newsom or his wife have friends or family who thought their children had been injured by vaccines? Did they know antivax quacks who wrote bogus medical exemptions? Is there a big donor who’s an antivaxer? What made him change his mind? It certainly wasn’t a good look.

Fortunately, by week’s end, an agreement was struck. In brief, the Governor agreed to sign SB 276 as long as the changes he wants are passed in a second bill, SB 714; Gov. Newsom will sign both bills into law at the same time. The agreement is definitely a mixed bag. Unfortunately, it includes Gov. Newsom’s mind-numbingly bad idea to grandfather in all existing medical exemptions before January 1, 2020, which will definitely spark a panicked gold rush for vaccine exemptions over the next three and a half months. SB 714 will also unfortunately remove a provision in SB 276 that would have required doctors to certify that medical exemptions are accurate, under penalty of perjury. (It’s almost as though Gov. Newsom doesn’t want any quack doctors to face penalties for perjury.) It would appear, though, that Sen. Pan wrung some concessions from Gov. Newsom. For example:

However, Newsom’s amendment contains a key caveat: New medical exemptions would be required when a child enters kindergarten, seventh grade or changes schools. By adding that provision, permanent medical exemptions would no longer be valid throughout a child’s K-12 education. A similar approach was used when the state eliminated personal belief exemptions in 2015 under another bill by Pan that allowed immunization waivers to remain valid until a child reached kindergarten, seventh grade or changed schools.

There is also one new provision in SB 714 that actually improves SB 276. It’s a provision I wholeheartedly approve of:

SB 714, which is also written by Pan, would invalidate any medical exemption from a doctor who has faced disciplinary action by the state medical board.

Sears, who is currently subject to a 35-month probation order issued by the medical board in a vaccine case that did not involve school medical exemptions, expressed disbelief over the amendments released Friday.

“[This bill would] mean that any exemption written by a doctor who has been disciplined by the board for any reason, even one unrelated to vaccination, will be subject to revocation,” Sears said. “So the hundreds of patients I’ve written exemptions for over the past four years after having a severe vaccine reaction will lose their exemptions. This seems like a broad overreach from a government that is supposed to protect its medically fragile children.”

So, yes, the compromise is very much a mixed bag, but that’s politics, I guess. Certainly, the law in California governing school vaccine mandates will be improved after passage of SB 276 and SB 714 compared to before, but, man, the process was ugly and the Governor’s meddling was depressing to behold.

Several years ago, I occasionally got into—shall we say?—heated discussions over how far we should go with school vaccine mandates. It was always obvious that the closest to ideal policy would be to allow only medical exemptions, but my point was that, politically, it would be difficult to impossible to pass laws eliminating nonmedical exemptions. As a result, I tended to favor what I considered to be what was feasible, rather than pie-in-the-sky policies; in other words, policies like what we have in Michigan or California’s AB 2109, the goal being to make nonmedical exemptions as difficult to obtain as feasible. Such policies are admittedly halfway measures, but they do work, just not as well as eliminating nonmedical exemptions altogether. I believe that my assessment was correct, too, at least before the Disneyland measles outbreak. However, the Disneyland measles outbreak changed the equation, at least in California, making what was once not feasible suddenly possible, and Sen. Pan to his credit took advantage.

Even after that outbreak, though, eliminating nonmedical exemptions was still a hard sell, and there was a price to pay. The battle to pass SB 277 energized the antivaccine movement as never before. Worse, it led to an unholy union between small government conservatives and antivaxers, particularly in states like Texas, where antivaxers successfully politicized school vaccine mandates by appealing to conservative activists through language emphasizing “parental rights” and “health freedom” and vaccine mandates portrayed as governmental overreach. As a result, Republican candidates for office not infrequently find themselves feeling as though they have to pander to antivaxers, as they did in my own Congressional district, with the GOP being far too receptive to antivaccine arguments, far more so than Democrats.

Still, this is a battle worth fighting. Being in the midst of the largest measles outbreak in a generation has led a handful of other states to take the plunge and ban nonmedical exemptions, religious and personal belief, as I mentioned above. Even so, 45 states allow religious exemptions, while 15 states currently permit philosophical exemptions in the midst of this outbreak. We have a long way to go, and in the meantime we shouldn’t let the perfect be the enemy of good. I will support nearly any policy that will decrease the rate of nonmedical exemptions. Congratulations to Sen. Pan. He didn’t get everything he wanted, but he came close. And shame on Governor Newsom for playing politics with public health.